Within local waterways, you may have come across what scientists call an algal bloom: reddish, brownish patches in the water also called a red or mahogany tide.

The spots are caused by algae that rapidly multiply and suffocate surrounding marine life.

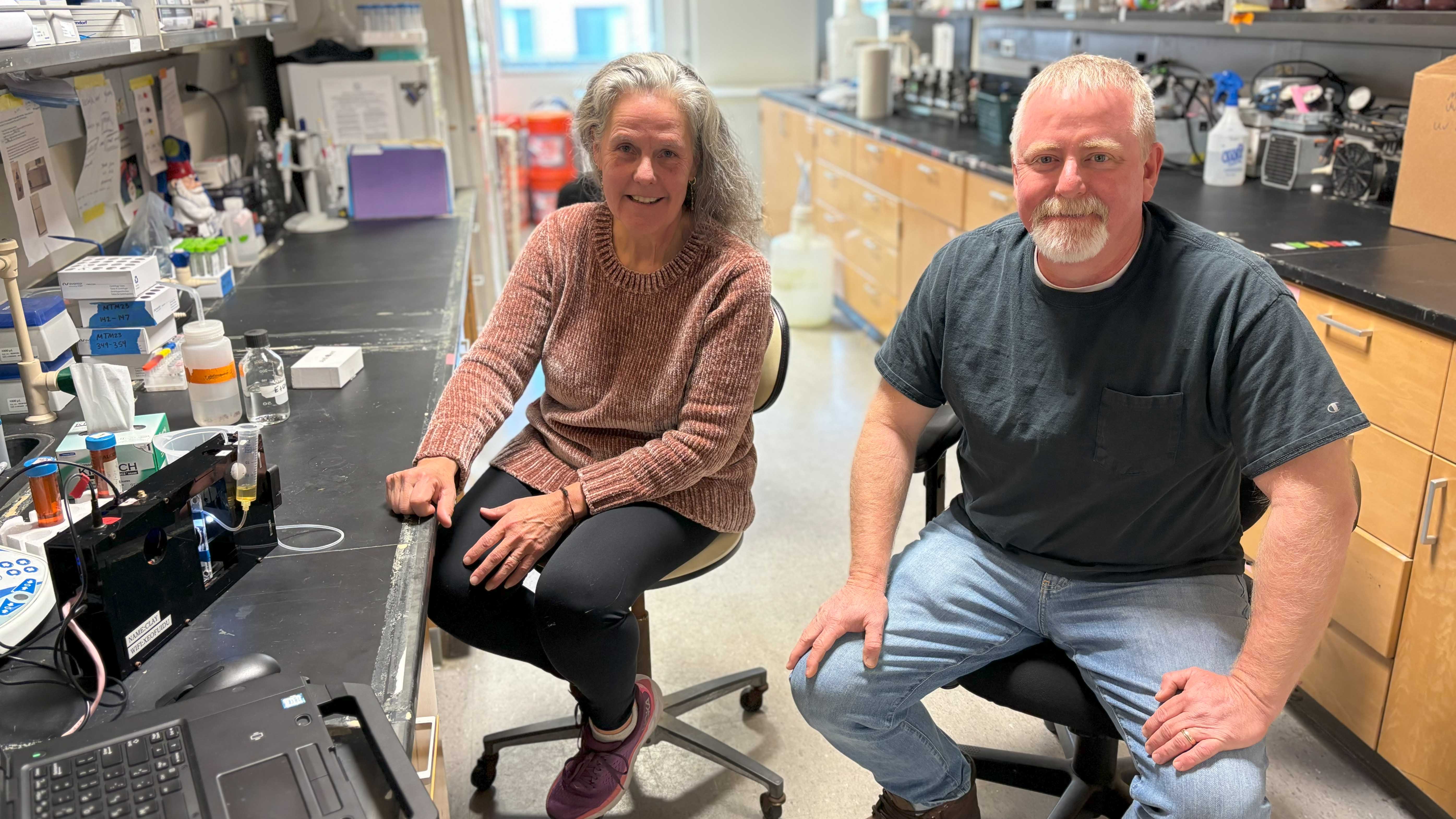

Old Dominion University professor Margie Mulholland studies the phenomenon, which is caused by polluting nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from sources including fertilizer, pet waste and detergents.

“When we add nutrients to the water, just like on land, they stimulate plant production,” Mulholland said. “And sometimes we have too much of a good thing, and we get harmful algal blooms.”

She’s now spearheading a five-year project she hopes will serve as an “early warning system” for local algae blooms.

Her team, which includes scientists with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, recently got a $3 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to do so.

Currently, it takes a while for scientists to collect a sample from an algae bloom, take it to a lab, look at it under a microscope and manually count each organism in the sample to determine the species present, Mulholland said.

She aims to speed up that process from days to minutes.

The project centers around a new device called a PlanktoScope. Developed at Stanford University, the open-sourced device can be assembled using materials from Amazon for a couple thousand dollars. That’s vastly cheaper than existing imaging systems that can cost over $100,000, Mulholland said.

Lab manager Peter Bernhardt demonstrates a sample moving through the Planktoscope device.

On a recent visit to the ODU lab, lab manager Peter Bernhardt demonstrated how the Planktoscope works.

The user simply adds a small sample of water to a syringe and a pump moves it through the digital microscope, instantly sending images to a corresponding computer, tablet or even smartphone.

“It’s very easy to use for someone that may be new to it, (like) citizen scientists,” Bernhardt said.

Mulholland pointed to the computer screen, which displayed dozens of images of bean-shaped algae cells.

“Using computer programs and machine learning, you can train your database to identify the species in this,” she said.

A computer screen at Margie Mulholland's ODU lab displays cells of a harmful algae species.

By the end of the research in 2028, Mulholland hopes to have a working system that could be used in real time by health and environment officials in Virginia.

“When someone sees discolored water, we get someone in the field and they can analyze a sample … and report to us whether there are harmful species in the population at that time,” she said. “We can send out warnings so that people can avoid contact with that water.”

The problem is not going away anytime soon. Climate change is warming the Chesapeake Bay, spurring the growth of these algae.

The biggest concern is that the blooms cause “dead zones” with not enough dissolved oxygen in the water. The algae take over the water’s surface and block out sun from reaching life that needs it below.

“We're very concerned with fisheries resources being at risk, as well as tourism and other activities,” Mulholland said.

The biggest harmful algae blooms often happen in shallow tributaries of the bay, like the Elizabeth River and the Hague.