Virginians have hunted deer and bears using hounds for centuries.

The tradition has benefits for wildlife management and recreation, state officials say. But they also say they’re seeing rising conflict between hunters and landowners who don’t want dogs encroaching on their property.

“This is the most common complaint that the department receives,” Cale Godfrey with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources told a state board earlier this year. “Frequent, repeated instances of unwanted dog presence are the source of many of those complaints.”

State officials are now weighing new regulations on hound hunting. This week the department launched a public comment period on two proposals.

One would require GPS tracking collars be used on all dogs involved in a hunt. Most hound hunters already use the collars, which can cost hundreds of dollars.

DWR says the collars would allow hunters to know where their dogs are at any particular time in order to retrieve them when necessary – and to show where the dogs have been if that comes into question.

The other proposed regulation would require hunters to make “reasonable efforts” to keep dogs from entering private property if the owner or wildlife police have stated the dogs aren’t welcome there.

Kirby Burch, a Powhatan resident and CEO of the Virginia Hunting Dog Alliance, said he believes it would be “a first of its kind dog trespass law.”

His group strongly opposes the proposal, which focuses on repeat offenders whose dogs have been on a private property without permission at least twice within a year.

It’s unclear what the penalty would be. Burch worries the threat of a potential misdemeanor charge could keep people from the sport, which is integral to life in rural Virginia.

“A dog has a mind of its own” and can’t fully be controlled off-leash, he said.

“It’s just a convoluted attempt to end hunting with dogs.”

The state’s been studying and attempting to manage the issue since at least 2008. Most recently, DWR commissioned the University of Virginia’s Institute for Engagement and Negotiation to facilitate discussions with hunters, landowners and public officials.

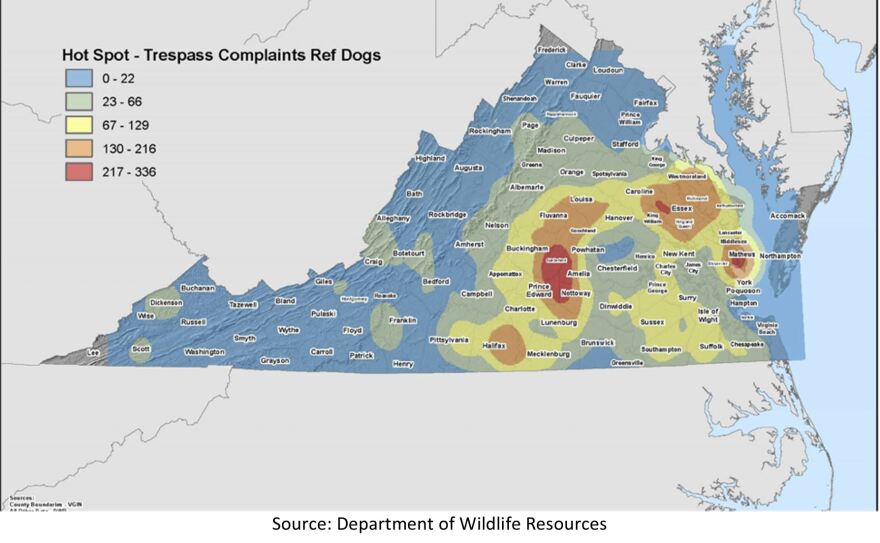

The institute found that conflicts between property owners and hunters have likely grown from factors like the rise of social media and population growth in rural areas. Hotspots for complaints include the Middle Peninsula and areas west of Richmond.

Past attempts to reduce the conflict “have resulted in little substantive improvement,” staff wrote in the report.

Other states have instituted measures on hound hunting like acreage limitations, permits and complete bans.

Attempts to get a permitting requirement or other restrictions through Virginia’s General Assembly failed repeatedly, including this year.

In March, the Board of Wildlife Resources held a special session on the topic, where they narrowed down seven proposals to the two now up for public comment.

Hunters and property owners showed up with passion on both sides.

“Property rights of Virginians have to be respected and protected or this will continue to spiral out of control,” said Chris Patton with the Virginia Property Rights Association. “Regulating hound hunting before it explodes into violence is the only way we save hound hunting in Virginia.”

Hunter Tim Goodbar said he sympathizes with property owners’ concerns but thinks the regulations are a slippery slope.

“I think what we're going down the road here is to do away with hound hunting altogether,” Goodbar said.

And “if it dont involve a hound, it ain’t hunting.”

Mike Foreman with UVA's institute said that everyone wants hound hunting to continue “if we can reach and achieve some measures to reduce the conflict that's involved.”

Burch, with the hunting dog alliance, said it’s “going to be a long fight.”

DWR is collecting public comments on its website, or by email and snail mail, through July 5.

The wildlife board will then review the comments before bringing the topic back onto its agenda.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story misattributed a quote by Mike Foreman to Cale Godfrey.