By Louis Hansen

The Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

In the wake of the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, elected leaders vowed to prioritize campus safety.

Then-Gov. Tim Kaine appointed a blue-ribbon panel and within a year signed more than 30 mental health, school security and gun purchase bills aimed at preventing future mass shootings. Several appeals for stricter gun policies, however, were voted down.

More than 15 years later, in the aftermath of another school shooting — this time at the University of Virginia, where three students were shot and killed in November — state lawmakers considered a range of gun policy proposals: a ban on new assault-style weapons, new punishments for those who fail to secure their guns, an expansion of the state’s “red flag” law and restrictions on possessing firearms in school buildings.

But just one major safety measure survived: a $300 tax credit for firearms owners to purchase gun safes. A second bill requiring public universities to more quickly and comprehensively respond to a potential threat passed the House and Senate but still awaits Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s signature.

With control of Virginia’s General Assembly divided politically, the stronger gun measures never cleared both chambers.

“We don't have mature conversations about guns,” said Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Bath. “We gather up in tribes.” Deeds had long opposed further restrictions on gun ownership but this year introduced a ban on new assault-style weapons.

“On the gun control side,” said Philip Van Cleave, president of the Virginia Citizens Defense League,“they’re basically batting zero.”

But experts and a survivor of the Virginia Tech massacre say there’s more to bringing safety to schools and campuses than gun control. Virginia schools, they say, have made progress but still have work to do.

Many Virginia colleges, including UVA, ban weapons from school property, although it is not necessarily a criminal offense. Others, like private Liberty University in Lynchburg, allow firearms.

After the November mass shooting, UVA officials asked lawmakers for stronger protections in state law to enforce their ban. But measures to make it illegal for unauthorized people to bring weapons into buildings operated by state colleges were defeated.

An analysis of reported weapons violations on university campuses by the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO shows a relatively stable number of citations since the Virginia Tech shootings.

Since 2009, law enforcement has reported 757 weapons violations on 30 Virginia campuses. Violations peaked at 79 in 2010 and fell to 38 in 2021, the latest year statistics were available from the Virginia State Police.

Urban schools — Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond and Old Dominion University in Norfolk — have the highest instances of weapons charges, according to crime statistics. Between 2009 and 2021, VCU had 439 violations — 58% of the total — and ODU had the next highest number with 80.

UVA reported 28 violations, and Virginia Tech had 32 during the same period, according to the analysis.

Andy Pelosi of the Campaign to Keep Guns off Campus said state lawmakers around the country have been less willing to take up new gun safety measures in recent years, despite the recent high-profile mass shootings.

“We’re not seeing real solutions legislatively to address these issues,” he said. “What we really need to have is a cultural change.”

Deeds sponsored a bill with UVA support to make it illegal to carry a firearm in any building operated by a state-owned college. It also would have given university police the power to obtain search warrants when they believe firearms are being illegally possessed in university buildings.

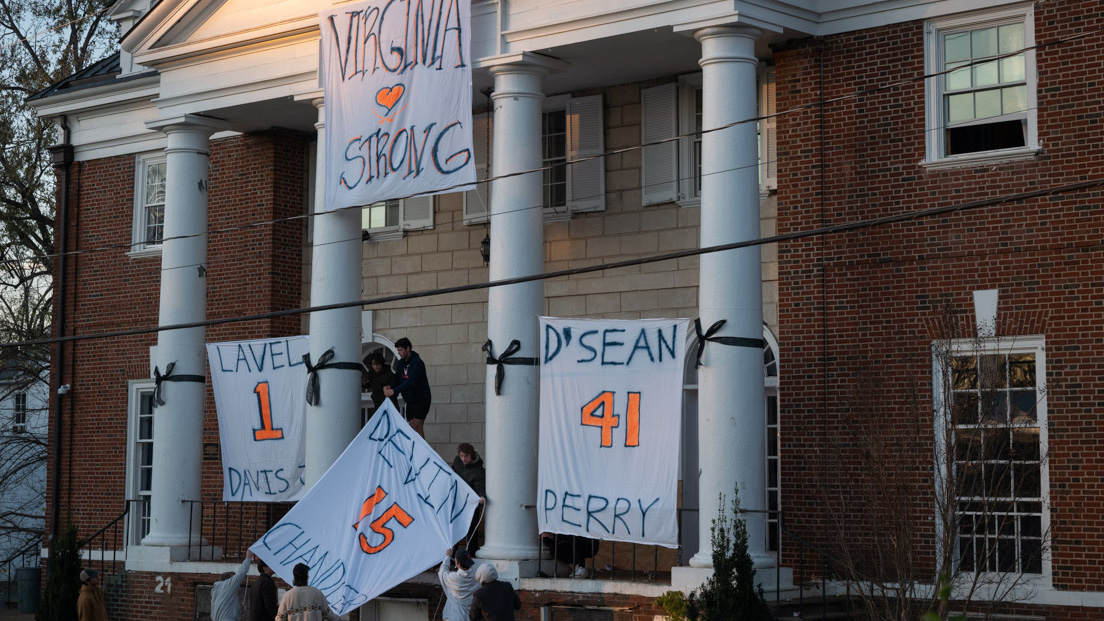

University of Virginia students hoist a banner over the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity following the slayings of three student athletes in November 2022.

Deeds believes the measure could have helped prevent the UVA deaths. A search warrant after the slayings found a small arsenal of weapons in accused shooter Christopher Darnell Jones Jr.’s dorm room. Campus law enforcement officials said the school had been alerted months earlier that Jones may have had firearms, but an initial investigation did not uncover evidence.

“Perhaps some law enforcement agency could have obtained a search warrant to search the property, could have found the firearms,” Deeds said. The bill failed to make it out of a House committee.

With few gun safety measures taken in the General Assembly since the Virginia Tech massacre, much of the work to make campuses safer has come straight from universities. The legislature passed a bill in 2008 that required state colleges to create campus threat assessment teams and establish crisis and emergency management plans.

One Tech survivor and a VCU psychiatrist who served as a member of the blue-ribbon panel investigating the tragedy said Virginia school and college administrators have learned how to make campuses safer since the 2007 shootings. Yet they acknowledge the need for better responses, education and mental health resources.

Kristina Anderson Froling was wounded by three bullets and traumatized by the April 2007 attack that took the lives of 32 people and the troubled gunman. Months after the attack, Froling started the nonprofit Koshka Foundation for Safe Schools to advocate for better campus security and training for students, faculty and administrators.

The stark lessons from Tech brought safety improvements, she said, which have been adopted by other schools. Physical changes to security — including classroom doors that lock from the inside and barriers and electronic systems that limit unauthorized access — have been widely instituted, Froling said.

“We realize that we cannot take safety for granted,” she said. “And school districts across the country became a lot more involved in bringing in community members, outside departments, agencies, outside vendors.”

But, she said, there is still a need to better involve the entire community to identify troubled individuals before they become violent.

“To be honest, there's still quite a bit of ways to go,” Froling said.

“If we have any hopes of prevention, successfully averting future attacks, we need parents that trust the school system enough to come forward.

“We need to make sure that our schools’ threat assessment teams have enough training and funding, and sometimes just institutional support,” she said.

Dr. Bela Sood, a clinical psychiatrist at VCU who served on the Virginia Tech blue-ribbon panel, said spotting early signs of troubled mental health needs to begin at home with close family members.

Before his alleged rampage at UVA, Jones, a fourth-year student, was the subject of harassment and had been cited for illegal possession of a concealed weapon, according to reports.

“I am sure that someone in this young man's life must know that he was troubled,” Sood said. But state laws make it difficult to bring patients into mental health treatment unless they pose an imminent danger, she said.

Jones is accused of shooting three student athletes — Devin Chandler, Lavel Davis Jr. and D’Sean Perry — and wounding two others in the attack. He remains in custody, charged with three counts of second-degree murder.

“I wish that we somehow began to get around this, because how does someone get to the point that they are in a pressure cooker of some kind, and the thing just blows,” Sood said. “Why aren't we able to do anything?”

Weeks after the UVA shootings, six Walmart employees were killed by a supervisor in Chesapeake. In January, a Newport News elementary school teacher was shot by a six-year-old student.

Yet a wall of resistance to changing the state’s gun laws remains.

Van Cleave of the Virginia Citizens Defense League has been arguing for gun rights in Richmond for the better part of two decades. He organized a rally at the state Capitol in 2020, drawing thousands of activists, many in full battle-rattle, to confront legislators who were primed to pass tougher gun regulations. Lawmakers withdrew some of the most restrictive measures.

Recent shootings should not alter the debate, Van Cleave said. Most people, he said, can see through the heightened emotions and reject curbs on a constitutional right.

“Let’s change the world because of one event?” he said. “That’s the quickest way to lose your rights.”

The political division in the General Assembly — the Senate is controlled by Democrats, the House by Republicans — ensured another year of stalemates on gun legislation.

The Virginia Citizens Defense League has maintained its staunch opposition to red flag laws, arguing that they do not allow a full, due process before taking weapons away. Those laws, adopted by about 20 states, allow guns to be taken by court order from those deemed to be a danger to themselves or others.

When it comes to campus shootings like UVA, Van Cleave said new laws wouldn’t necessarily have changed the outcome, he said.

“Some things you just can’t prevent,” he said.

But Deeds said legislators should have done more, noting opportunities in 2020 and 2021 when Democrats controlled both the General Assembly and governor’s mansion. “There will come a time again when we'll get things done.”