The WFMT Radio Network’s program 'Recovering a Musical Heritage' introduces listeners to Viktor Ullmann, the composer of Der Kaiser von Atlantis. Ullmann composed the opera in Terezín, a hybrid ghetto and concentration camp that housed more than 60,000 prisoners at any given time, mostly Czech Jews. This feature explores musical life at the compound, which thrived despite dreadful living conditions and constant Nazi surveillance.

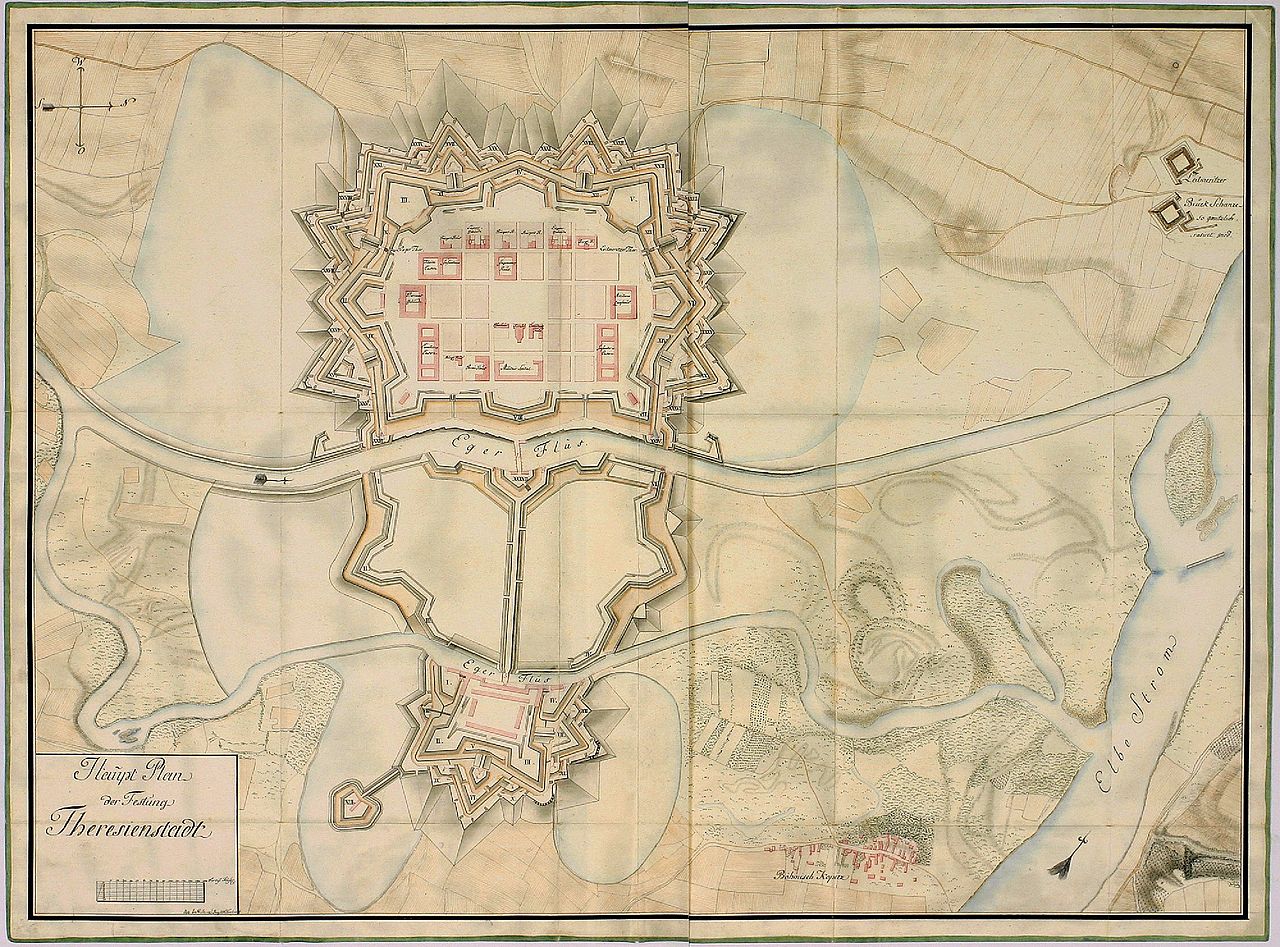

A 1790 map of the Theresienstadt fortress

A converted military fortress 40 miles northwest of Prague, Theresienstadt (or Terezín in Czech) is rightly remembered as the site of one of the darkest chapters of the Holocaust. In June 1944, a delegation from the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Danish government toured the hybrid concentration camp and ghetto, but, duped by a massive Nazi cover-up, infamously concluded that life there was “almost normal.” Unbeknownst to the delegation, by the time the war was out, 33,000 inmates would have died at Terezín, while for another 88,000, it was the penultimate stop before a death camp.

At one point, the Nazis brought the delegation to a production of Brundibár, a charming opera by Hans Krása (1899–1944) and performed by interned children. But neither Nazi officials nor the international delegates quite understood that they were actually witnessing an act of resistance.

Aided by a large influx of Czech creatives and intellectuals, Terezín became the crucible for some of the most pointed art about the Holocaust, of which Brundibár was just one example. The musical life of the camp in particular was astonishingly rich — and often covert.

Theresienstadt, an unreleased propaganda film made around the same time as the Red Cross visit, documents a production of Brundibár.

The story of music at Terezín dates back to the Nazi creation of the camp itself. With the Final Solution underway, Nazi officials knew they would need a cover to conceal the extent of their plans, so they branded Terezín as an all-Jewish “resort” town. As such, it was initially only open to Jewish men who were senior citizens, decorated military veterans, and social elites, all of whom were allowed to bring only a few essential personal possessions into the camp.

The first transport — or Aufbaukommando — arrived voluntarily at Terezín on November 24, 1941. Instead of the lively town they had been promised, however, the deportees who arrived first found old barracks, barren streets, and a total lack of amenities. They were tasked with preparing the rest of the camp for future inmates, the first thousand of whom arrived just a week later.

Those in the early wave of arrivals must have had the foresight to pack their musical instruments, because the first surviving artifact documenting a musical program at Terezín is dated December 6, 1941 — just two weeks after the arrival of the first Aufbaukommando. The program credits a flutist, two violinists, two accordionists, and even a jazz orchestra — all the more remarkable given that instruments would have been forbidden as “non-essential items.” (It’s said that one man even disassembled his cello so it would fit in his luggage, then reglued it inside the camp!)

It’s unclear how much the Nazi officers knew about these early performances, but it’s likely that they were ultimately tolerated to maintain morale and quell potential uprisings. Similarly, in 1942, elders from the Aufbaukommando organized the Freizeitgestaltung (Administration of Free Time), approved by Nazi officials. It became a key coordinator of the blossoming recreational and cultural activities in the camp, even as living conditions deteriorated.

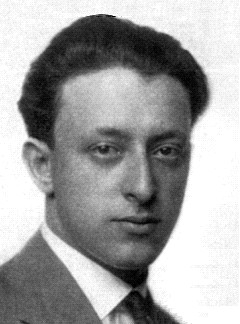

Rafael Schächter

Formerly a music director in Prague, Rafael Schächter (1905–1945) quickly emerged as one of the most active members of Terezín’s musical community. In the camp, Schächter spent long hours transcribing choral numbers from smuggled score sheets, reading through them with makeshift choirs. His dream was to bring opera to Terezín, especially The Bartered Bride, the most beloved of Czech operas. He succeeded in November 1942, conducting a concert version of Smetana’s comedy from behind a legless baby grand piano (which had also been smuggled into the camp).

The audience was deeply moved by the performance, so much so that the opera was repeated some 35 times over the next several months. “I have heard The Bartered Bride three times in Prague, but it was never so beautiful as here,” attested a 13-year-old witness in her diary.

Schächter led prisoners in other repertory works like The Magic Flute and The Marriage of Figaro, but he eventually explored more charged repertoire. He led about 15 performances of Verdi’s Requiem at Terezín, including once for the infamous Red Cross delegation. The sentiment behind the “Dies Irae,” with its promises of a day of reckoning for the wicked, was all too clear; no records show that Schächter ever conducted the Verdi again at Terezín.

Astonishingly, Schächter wasn’t the only one leading large-scale choral works in Terezín. His herculean efforts inspired other artists to do the same: Terezín audiences would have heard not just oratorios like Haydn’s Creation and Mendelssohn’s Elijah in the barracks, but ambitious operas like Rigoletto, Tosca, and even a fully staged Carmen. They also had a critical mass of professional singers, with regulars from the Vienna State Opera, Netherlands Royal Opera, Brno Opera, and more living there.

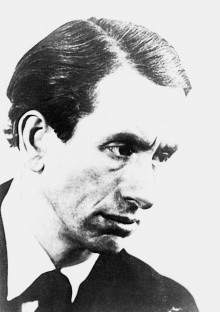

Pavel Haas

Instrumental music also flourished at Terezín, with ensembles ranging from string orchestras to swing bands. Surviving posters even document frequent recitals, which promoted works new and old. Pavel Haas (1899–1944), once a student of Janáček’s, composed a number of chamber works during his imprisonment that were popular among musicians, most of all his bracing 1942 choral work Al S’fod (Do Not Lament).

Viktor Ullmann

All record of these ambitious undertakings might have been lost without the steady pen of Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944). A critic for one of the camp’s many underground publications, he attended and wrote about countless musical events in Terezín, but his true passion was composition. Ullmann wrote one of the major works to survive from Terezín, a sardonic opera entitled Der Kaiser von Atlantis (The Emperor of Atlantis). The young writer-illustrator Peter Kien — himself an avid chronicler of camp life known for his inked portraits of other inmates — wrote the libretto.

Ullmann and Kien’s concept was incredibly subversive. In Der Kaiser, the wicked Emperor Überall announces a universal war until there are no survivors; Death, protesting this, goes on strike, halting the fatalities. After much deliberation, the Emperor trades his own life for Death’s return. The allegorical parallels are underscored by Ullmann’s use of a modal version of the German anthem, “Deutschland über alles.”

Ullmann had orchestrated the score specifically for musicians in Terezín, intending to have the first performance of the opera in fall 1944. Some sources say the production was halted by Nazi authorities during rehearsals; in any case, it never came to pass.

If it had not been exploited as propaganda fodder, Hans Krása’s Brundibár might have suffered a similar fate. The opera follows two children who are trying to buy milk for their ill mother. Broke, they decide to busk in the town square for money, but are chased away by a cruel, mustached organ grinder named Brundibár. Eventually, the children join with animals and a crowd of other children to stand up to Brundibár. As with Der Kaiser von Atlantis, the opera has a trenchant double meaning, down to Brundibár’s mustache.

Krása had actually composed Brundibár for children at a Jewish orphanage in Prague, where the opera was set to premiere under Schächter’s baton before the first wave of deportations in fall 1941. But he and Schächter were sent to Terezín, as were all the children and the entire orphanage staff. Undeterred in their new environs, the group reunited that summer to recreate the opera. Brundibár’s Terezín premiere in September 1943 was wildly popular: It was performed an unprecedented 55 times, and inmates even bartered for tickets.

Brundibár’s run continued until September 1944. That fall was the beginning of an especially dark time for the camp as the Nazi’s Final Solution reached its murderous zenith. Between September 23 and October 28 of that year, some 23,500 people were transported from Terezín to Auschwitz in an eleventh-hour push. On October 16, 1944, Schächter, Haas, Ullmann, Kien, and Krása were all sent to Auschwitz, in the same transport as other camp musicians. All died there.

Members of the Freizeitgestaltung were also deported, leaving the camp’s organized musical life in disarray. Some musicians — mostly women — kept musical life in Terezín hanging by a thread until the camp’s liberation on May 8, 1945.

But the loss was incalculable. Of the 144,000 people who would pass through Terezín, only about 23,000 would live through the war.

Hans Krása

In the years since, concert programs and performing arts institutions have brought the music heard in Terezín out of the shadows, thanks in part to initiatives like the Terezín Music Foundation and the Defiant Requiem Foundation. Krása’s Brundibár has been heard in performances all over the world, sometimes even with members of the original Terezín cast, and after being premiered at the Dutch National Opera in 1975, thirty years after Terezín’s liberation, Der Kaiser von Atlantis is also performed widely.

The music of Terezín is no longer hidden behind fortress walls or manipulated as propaganda. Performances of these works do some small part in keeping alive the memory of those who perished — a testament to their bravery and the resilience of the human spirit.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on wfmt.com.

On Monday, January 27 at 9 p.m., in recognition of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, WHRO FM will air a special program from WFMT: Recovering a Musical Heritage.

This year also marks the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Please join us on WHRO FM or listen online live for this special program.